In the ancient apse of the church of St Boniface, the group of works by Monika Fioreschy has been given a showplace which graces the works with 1400 years of Benedictine tradition and an even older architectural formula. Originally, the rounded end of a basilica, literally the 'hall of the king', served the judge or consul as an dignified seat and covered his back (literally) against importunate clients. Today – or at least that is the intention – the apsidial background formation will cover the backs of the works (metaphorically) against the insistent expectations of an art-loving public.

The church's patron St Boniface, who has gone down in the history books as the 'Apostle to the Germans', already had a hard time liberating the Teutonic tribes from their heathen ideas and putting an end to idolatry. And that is precisely what is intended today, for every visitor to the exhibition will quickly notice that artworks are mostly talked about in the same terms as the ancient idols, with art-lovers bowing down before them just as worshippers approached the idols of old in a spirit of obeisant submission. Today, the idols are known as 'artworks' – a provocative term to which at least we still react, while genuine cultic images are largely ignored.

Some 1200 years after Boniface, then, there is a need to free ourselves from idol-worship, this time from the idol-worship of art. Some 1500 years after the founding of the monastic communities by St Benedict and his sister Scholastica, the motto of the order is still 'ora et labora', a unity of 'prayer and work' which can continue to be read in modern houses of prayer, even if they look like factories or machine-gun emplacements, in which case it is the unity of 'pray and produce', or 'pray and shoot'. Some 600 years after St Boniface, artists began to develop theories of their own. The vocabulary they employed to describe their own Works was taken, almost without exception, from theology, and to this day, nothing has changed in this respect. And so there is still no secular art: on the contrary, the positively fundamentalist demand that artworks be worshipped is stronger than ever. Still unsurpassed, however, is the arrogance of a man like Albrecht Dürer, who around 1500 portrayed himself as Christ, thus laying claim to the succession of Christ for himself as artist. Not even the drawing of the crucified Christ in a gas-mask, which earned George Grosz a trial for blasphemy, was even remotely as scandalous as Dürer's self-portrait.

Among the most important of the formulations adopted from the language of theology is the concept of 'creative', which of course is related to the Christian God, the creator mundi. True, the artists took their inspiration from the contexts of everyday life, as had once been done by the stigmatised priests who preached water and quaffed wine, but the cultural experts, art interpreters and picture exegetes were later arrogant enough to raise themselves to the status of true keepers of the theory of creation. Art critics and historians did not even blush with shame when they identified splashing a bit of paint on a canvas as a great creative design by analogy with the divine creation of the world.

The most important thing about this story is that the artists themselves presumably have never noticed how they contributed towards the founding act of their own kind of 'praying and working' by following on from the creator God and, like Him, created their works totally unconditionally and purely out of their own wanton wilfulness. This circumstance is unique in the intellectual history of the last 2,000 years – the iconoclastic controversies of the eighth or the universals dispute of the twelfth and thirteenth centuries pale by comparison – because the public too really did believe that they, having gone through the Enlightenment, were turning their backs on idols. In practice, however, only the place of worship has changed: where once it was the church, today it is the museum or gallery. What was rejected as the spectre of retarded 'hostages of the priests' is being consummated once more in the secular exhibition rooms.

The presentation of artworks in a church creates precisely the link to a place where the original founding theology for artistic activity was worked out. Any insight into these associations can however only lead to all of us crazy faith-shaken, redemption-craving, salvation-awaiting Pauls of art becoming Sauls once more. For the most important faithful in our time are precisely those who have converted back from Paul to Saul, because they have their experiences behind them; they know what was and is at stake.

This is true not just of art, but also of events. In 1989 the communist system collapsed. Many of those who still galloped around as leaders of proselytising pep groups or political propagandists certainly noticed how they were losing their apparatchik power; how in just a few weeks everything would be over. To convert quickly from Saul to Paul in such a situation is no great feat. But to go in the opposite direction – especially when one is a talented artist, when the creative act flows directly from nature to paper because one thinks with one's hands and can see with one's fingers – now that is really something.

Monika Fioreschy has achieved this real something, and translated herself back into a Saul. She has liberated herself from the extortionate requirement that her work be art before which one must kneel in prayer. She has consciously turned her back on the party tricks and smoke-and-mirrors of the constant self-referentiality of works to each other and among each other. All Fioreschy does is to present a piece of perfectly ordinary work. Everyone works, and here we now have the chance of qualifying a particular way of working with respect to the requirements that arise from the historical context of Christian, and specifically Benedictine culture. From the earliest times, the Benedictines had been the most important order for the development of arts and sciences with reference to the history of the Church as an institution, as is manifest in the forms of architecture we can experience here.

With its origins in secular Roman buildings, the apse became a component of sacred architectural language and is now turning full circle, just as the Church has become a secular institution, an institution of secular life – without having become any less important as a result! The Church becomes important precisely insofar as it takes it upon itself to make the normal, the obvious, the self-evident into a problem, instead of asserting that it had personally received some mission or other from a higher place to demonstrate to us with magical airs. This makes the churches important institutions: the strength and the courage to face up to the everyday impositions, to serve those who cannot simply fly away or take refuge in ideological hocus-pocus or fairy tales. The churches are secularising themselves, just as artists are secularising themselves, by returning once again to the scale of a worker's ordinary activities and thus retaining their significance.

The obvious main motif in Fioreschy's works comes across in another way too when one sees it against the cultural-historical background of the church and theology. I'm talking about blood. Not least as a result of biographical serendipity (her husband is a heart surgeon), the artist has gained insights into a discipline which, alongside art, has advanced to the status of another modernist post-ecclesiastical institution, namely medicine. Here it has become clear how 'salvation' has been helped along its way by 'healing' (and in German the two words are the same). Heart surgeons in particular pursue this end at great effort and expense!

Like the architecture of a church, which creates the visible setting for baptisms, marriages and Sunday services, visible blood substances are used in the secular space of the earthly healing or salvation story: patients are linked up to machines via various tubes, and during the healing processes blood flows through them – reifying the inspiration of new breath, the preservation of life, by the surgeon. Like the artistic self-concept of the Imitatio Christi, the art of healing takes its legitimation from the theology of the church. At Holy Communion, for example, we hear the words: 'This is my blood.' For many people today this is still not, or no longer, comprehensible. In an operating theatre, however, it becomes clear what this actually means: a patient who has lost a lot of blood is given the blood donated by someone who has lain on a couch in a Red Cross station 'Here, take my blood.' This in a way concretises and secularises the great words of Christ, bringing them down to earth. We can be sure that no one thought of this before blood transfusion was developed. The important thing about such words, though, consists precisely in the fact that – unconstrained by the concrete givens of a particular situation – they can have validity in a wide range of different spheres of human physical or psychological life. It is therefore not degrading if the spirit of 'this is my blood' is conveyed today through cardiac surgery.

Fioreschy has now collected a large number of tubes from the healing (or salvation) context of the hospital, and interwoven them, a technique she had previously tried out as a artist working in the textile field. By fixing the position of juxtaposed blood-filled tubes, she creates textile-like structures, new surfaces, including all-over structures, in other words forms that evenly fill out the whole field of perception, in which, however, one can make out in turn individual details, distinctions and shadings. The degrees of redness or paleness are a consequence of the aging of the blood in the tubes: the older the material, the paler it becomes. In order to get one's bearings in the weave of the world, it is helpful to be able to make such distinctions in the first place.

The theological dimension in Fioreschy's works consists in the fact that she succeeds in creating a link between theological argumentation with respect to 'this is my blood' and our current everyday practice, without mitigating the theological dimension or devaluing the artistic act as service to the church. It is precisely this transfer that we can expect from artists if we do not regard them as bringers of salvation from other worlds, but ask them what we can find here on earth in the way of solutions to general problems.

Anyone turning away again from these works, having understood that here, someone is appearing not as an artist in the sense of theological smoke-and-mirrors, not as a creator ex nihilo by analogy with God, not as an autonomous individual subject, but as a human being like any other, with certain difficulties in joining up the challenging historical or theological positions. Those who have understood this are doing precisely what can also only be expected of an artist: the unlocking of a clear and clearly defined set of problems by the use of particular methods.

Here, just as clearly as in the operating theatre, where the transfer of enlivenment becomes possible, the conclusion to be derived from the long submerged formula, now only significant for spiritualistic minorities, is revealed: 'This is my blood'. There are no references to anything that can be discussed beyond this concrete set of problems. No ideological or art-theoretical positions or aesthetic issues are superimposed. The works represent the simple attempt to present a problem, a possibility of encompassing something which seems to everyone else to be highly ambivalent if not already lost. Suddenly, seeing pictures is taken just as much for granted as reading the newspaper, something totally normal and everyday. The pictures have the power, in this banality, to open up immediately to all who have ever seen them: a total theological context at a modern secular level.

The works of Fioreschy are an occasion for awareness: totally calm, unpretentious, devoid of pathos. We stand before them and find ourselves able to address an incredible expanse of a horizon (a theological-cultural-historical horizon in this case) in today's world of everyday experience – and at precisely the level of aspiration that corresponds to everyday expectations.

This should be an underlying idea: to gear one's own work, here addressing the theme of healing and salvation in the two dimensions of church and clinic, to a particular task. In this limitation lies the possibility of disillusioning the numerous Pauls of art and enlightening them through this disillusionment. This has been the purpose of illusions in art for ever and a day: to demonstrate the illusion through dis-illusion-ment and making it rationally and emotionally testable for everyone (cf. Nitsch, well-understood as he is).

Anyone can put himself or herself into the situation of lying in the chamber of curiosities of a clinic; the process of questioning then becomes as normal as humanly possible, as comprehensive as humanly conceivable. It puts an end to such questions as 'Is this art or isn't it?' And 'if it is art, then why?'

We just look, and in the very act of posing the problem we create a link with theological associations, or not as the case may be. That's all. And precisely this should be the goal in modern secularisation training. Of course, everyone is madly keen on secularising the residues of cultural history which cannot be instrumentalised, and those who are keenest, namely the apparatchiks, academics and so-called experts don't even consider the possibility of secularising themselves. True, they speak of how priests have to be ground into the dust, or the churches thrown on to the rubbish tip, but it is only in order to create a more portentous throne for themselves.

A sensible, useful and total secularisation, however, means liberating oneself from the inappropriate expectations and rigid demands made of artists and their few squiggles on paper, for only then can one at last stop moaning about what doesn't succeed. It is otherwise too embarrassing if even the alleged greatest, for example Mr Marx in the form of his busts, or pictures by Georg Baselitz, degenerate into mere decor. These falls will not happen if we do not invest artists and their easel works with expectations of magical salvation in the first place. To this end, we have to say goodbye to the attitude of impelling artists to make their daubing even crazier, even more lost to the world, even more surrounded by fantasies of omnipotence and to elevate art into something magic, magnificent and unique – something that can in any case only be realised by a tiny number of geniuses. The question: 'And that's supposed to be art?' cannot be put radically enough in view of the secularisation processes that result in raising values on the art market or obtaining for the artists an entry in the encyclopaedia.

We have to be still far more Saul-like when we ask what artistic work means in comparison with what everyone else does in daily life. The avowed Pauls of the great one-off success must become Saul-like acknowledgers of failure, for, as is well known, people only learn from failure; success plays no part in the process. We all experience failure, powerlessness, the non-fulfillability of expectations.

For artists too, failure is the only form of success, and the whole history of modernism is, when looked at properly, nothing but a demonstration of this objective fact. And this brings us back to theology, for this formulation could, without much change, have a place in every Sunday sermon, in the sense of a generally understandable speech within a particular common experience as Christians.

This was also the basic idea behind the series 'The Hour of Art' in Munich's St Boniface parish in 1996. With Fioreschy's artworks as the foundation, the various positions of experts from a wide variety of different spheres were examined in the context of central concepts from the theory of art, and in the process important theological ideas were rediscovered.

The link between these standpoints can be made in the same way as one can make the link between organism and source of help with the transfusion tube. Now many people say when confronted with great works of art, that their 'heart stands still'. But it is precisely then that they need such tubes, such by-passes. With this series of events we are building a few by-passes, relief-roads, for those suffering from high art pressure, so that they can return to the level of a rational, sceptical Saul; so that they can continue to ask artists why they do not succeed in the things we think them capable of; why they do not succeed in being a genius of revelation, or feel themselves in the Imitatio Christi; why they do not succeed in placing a sweeping gesture of world creation on the wallpaper in a unique act of skill. If the artists show why they do not succeed, they are informative, and they can be informative not least because to fail at their level does not have any irreversible consequences. Not like a heart surgeon: if he fails, it does have irreversible consequences: the patient dies. For this reason we cannot adduce his profession or that of the politician or the therapist or the engineer in the same way to exemplify failure as a form of success. Those who practise these professions must, on the contrary, gear themselves to constant success and achievement of perfection. In fact they themselves are mostly the most detached sceptics and the greatest cynics, doubtless not least because they would otherwise not be able to stand up to the constant pressure of the demand for perfection, for the Imitatio Christi, for godlike creativity, because they too can only do what is humanly possible.

Art is so powerful precisely because the demonstration of failure as a form of success is possible without damage to third parties, without a fatal outcome for the client.

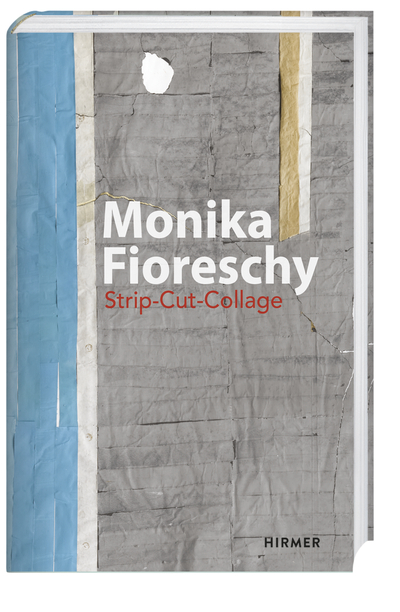

First published in: Monika Fioreschy, Stunde der Kunst, Munich 1997