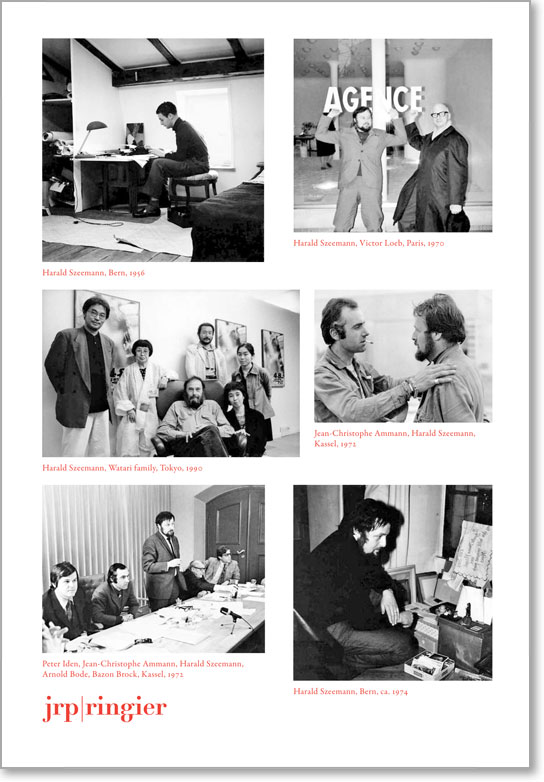

These interviews were conducted by phone, e-mail, and postal correspondence between March and June Harald Szeemann’s collaborators kindly answered our questions concerning their respective contributions and experiences, namely Jean-Christophe Ammann (Realism section), Bazon Brock (Audiovisual Preface section), Francois Burkhardt (Utopia and Planning section), and Johannes Cladders (Individual Mythologies section).

LUCIA PESAPANE

documenta 5 was not only an artistic event, but also a political debate in terms of its content and the way Harald Szeemann changed the rules about the way it was run. Szeemann himself was appointed General Secretary, which underscored the notion of independent curator. Did you have the feeling you were part of a team? How was the selection done? Did you choose the artists in your section, or was it done with Szeemann?

JEAN-CHRISTOPHE AMMANN

I was co-organizer and curator. I selected the works for the section Individual Mythologies with Harald Szeemann and alone for Realism. I was involved very little in the team. I worked only with Szeemann, intensely on the organizational level and, of course, on the communication.

JOHANNES CLADDERS

Harald asked me to curate a department dealing with his idea Individual Mythologies. I did not agree because I believed that each work of art is an Individual Mythology. Harald accepted my position and he gave me absolute freedom to realize my own thinking. As part of this concept, I decided to curate the contributions of Joseph Beuys, Marcel Broodthaers, Daniel Buren, and Robert Filliou. For the catalogue, I wrote a text about them titled Die Realität von Kunst als Thema der Kunst (The Reality of Art as the Subject of Art). But I also felt responsible for a lot of the other artists in the section Individual Mythologies. The whole organization was a little bit chaotic and produced a lot of problems. Therefore my department was referred to internally as “difficult artists.”

FRANÇOIS BURKHARDT

Harald was surrounded by a group of advisers whom he’d appointed and who defined the theme of d5 with him (Jean-Christophe Ammann, Arnold Bode, Karlheinz Braun, Bazon Brock, Peter Iden, and Alexander Kluge). Then he called on certain authors for certain specific themes. In my case the subjection of the Utopia and Planning section was chosen by Szeemann and he specifically asked me to elaborate it as an architect and architectural theorist. In turn, I headed a team of my own choosing, composed of Lucius Burckhardt, Matthias Eberle, and Burghart Schmidt. Harald asked us to work on the theme of architectural utopias in relation to Pierre Versins’ Science Fiction section, and we were urged to make a distinction between science fiction perceived as “today viewed from tomorrow” and utopia conceived as “tomorrow viewed from today.” Based on those given subjects, we were able to develop our section in total freedom, proposing the projects that seemed most interesting from the social and urban-planning standpoint, notably those that concerned alternative types of town development for cities in the future. We decided to devote this section to the Marxist philosopher Ernst Bloch, who wrote a great deal about social utopias, so he provided the basis for our research.

BAZON BROCK

In 1972 I was responsible for defining sub-sections of d5 by devoting them to themes such as “The war of images,” “The claim of reality within images,” and “The relation between arts and images.” Beyond this, I developed a version of The Visitors’ School as an “action teaching” with mixed media (technically realized by my assistant Jeannot). I started by offering The Visitors’ School for exhibition events like documenta in 1968 (d4) and I continued with special versions of visitor schools within documenta in 1977, 1981, 1992.

All the participating artists were named by the different curators, but chosen by collective decisions and of course Harry Szeemann was the moderator-in-chief. The choice of a general secretary had become necessary as a matter of public relations; the journalists, politicians, and heads of visitor organizations wanted a single person in charge and on whom they could depend to answer their questions. Beyond this pragmatic aspect, the zeitgeist [spirit of the time] had changed and the interference of politicians as godfathers of documenta was no longer possible. The spirit of the time proclaimed that everybody had to shift from arguing in terms of structuralism into patterns of individualism. Being the chosen general secretary of documenta gave Harry Szeemann absolute autonomy with the only condition that he wasn’t allowed to spend money above and beyond the official budget.

LUCIA PESAPANE

You were, from the beginning, part of the conception of the first project for documenta 5, which was designed as a “100-day event” instead of “an exhibition of 100 days” because for you documenta was not a static collection of objects, but a “process of mutually interrelated events.” This first proposal was more radical and more similar to the Happening & Fluxus exhibition in 1970: why was it finally changed? By whom? How was the second project (Questioning Reality—Image Worlds Today) conceived?

JEAN-CHRISTOPHE AMMANN

I was involved in the second project right from the beginning when we were thinking about the 100-day event, but it was mainly a strategic idea, too expensive and too difficult to realize. What was wanted was the presence of the artists on the site, what was striven for was a space of interaction, a walk-through event structure with shifting centers of activity, a vast communal studio for the invited artists. Then the project switched into a thematically oriented exhibition.

BAZON BROCK

The change of concept was inevitable, because of the necessity to insure objects. The insurance agency was not prepared to differentiate between objects and environments as instruments for the visitors and those which should not be touched, or between areas as space for the audience and spaces for the artworks themselves. The simple answer is that no insurance company would accept a non-artistic installation of art objects, instruments, scientific demonstrations, performances, happenings, action teachings, and working classes for the audiences. Therefore we had to look for a completely new structure. For us historical examples came into play such as “Kunst and Wunderkammer,” Christmas markets, pilgrim hostels, world exhibitions, warehouses, and especially guided tours known as the “Grand Tour” in the 18th century. Mediating between the visitors and the exhibition meant rediscovering the historical character of psychopompo,[1] excavation guides, and and itinerant preachers. Therefore I developed a concept of itineraries, which were to be chosen one after the other by every visitor. The visitor was asked first to choose character of a tourist, then a connoisseur, and then a pilgrim. It was a way to educate by passing through different situations and stages.

LUCIA PESAPANE

Even while remaining free, Szeemann didn’t object to the institution of museums, which he exploited. According to him, documenta 5 could afford to abandon the illusory freedom of a “museum in the street,” and in fact he housed the show in and the Fridericianum and the Neue Galerie. Why?

FRANÇOIS BURKHARDT

Szeemann was right, we needed to get the best out of institutions by changing them in line with his fundamental concept of innovation. His message always involved using art in a forward-looking way. In pursuing that goal, the theme of utopia could rightly be considered a model for study when transforming the present.

Harry—like us, for that matter—didn’t view museums as a site of reproduction, but as a lab or workshop, a place for research in various fields which explored major social questions, the goal of which was to try to answer those questions through art. He was one of the most inspired curators ever, not only because he had a clear vision of what he wanted to do with art, but also because each time he approached a new project, he added new arguments that art should address. He knew how to grasp those major issues in contemporary society where art could intervene in a critical, positive way.

LUCIA PESAPANE

Harald Szeemann’s approach to the history of art is much more similar to ethnographic and anthropological studies, rather than the approach of an art historian. Some sections can be thought of as “Wunderkammer,” as a cabinet of curiosity, such as his archive. How do you consider this kind of approach to the world of art? Did you share his viewpoint? What were Szeemann’s selection criteria?

JEAN-CHRISTOPHE AMMANN

Harald Szeemann and myself were exhibition makers. We did not work primarily as art historians. We were both connected to the intensity of the work of art and the authenticity of feelings, we had strongly similar ideas. Harald considered himself more as an artist. He had a vision: the Museum of Obsessions.

JOHANNES CLADDERS

Harald Szeemann was not an art historian, nor a curator in the traditional sense, he was an artist. Daniel Buren said: “documents 5 is the art work of Harald Szeemann, and we, the artists, give him the materials to make it.”

FRANÇOIS BURKHARDT

Szeemann’s approach to the art world was always guided by a strong position vis-a-vis social reality, thanks to his acutely critical eye. He had a sociologist’s or anthropologist’s ability to examine contemporary phenomena, and in addition he was able to suggest new, alternative models—his own. That led to the complexity and multiplicity of d5: the difference between the themes was one consequence of the complex relationship between art and society. His inquiries were related to the possibility of changing things, what he thought would be possible via the reference models that included art. He had great confidence in art’s ability to point society down new paths—something that doesn’t happen any more.

BAZON BROCK

One of the sections of d5 was Individual Mythologies, a personal term and one of Harry Szeemann’s concepts: it expressed the subjective cosmos of every artist, more than giving an objective insight toward reality. With this notion he wanted to show different attitudes, more than one style. By this it became evident that we had to include in d5 such distinct forms of non-artistic imaging making as: images from journalism, scientific images, images as therapy, as advertisements, as fashion, as military technology.

LUCIA PESAPANE

In this multiplicity of points of view, Szeemann declared it was a democratic idea, leaving the spectator free to find his own answers. Different development phases were a way to force the visitor into a dialectic-didactic approach: to train viewers to sharpen their judgment through contradictions. Do you think this is the role of the curator: to actualize, to re-think, to re-link different aspects of reality and then to leave the spectator the possibility to share his view or to rebuild one by himself?

JEAN-CHRISTOPHE AMMANN

Yes! We built very well-organized spaces, sometimes as a whole, sometimes as little worlds with their own dynamics, but always involved in a larger dynamic of similarities and differences. It was up to the spectator to find his answer and his conclusions.

FRANÇOIS BURKHARDT

Szeemann didn’t want to propose a didactic concept in the strict sense, he preferred to leave people free to find out for themselves. What enriched this show was the group of co-workers itself, where everyone was free to make a creative contribution, one that was often transversal to the theme initially chosen by Szeemann. All these relationships, taken together, yielded a variety of presentations, visions, and interpretations that constituted a great school for visitors. They could come to their own conclusions. We ourselves were enriched by the experience; Szeemann didn’t impose his own knowledge, so documenta 5 was a collective process that included him, us, and the artists, via debates and discussions. Our efforts focused, in fact, on how to get Harald’s message across to visitors. He was very clear in his mind about his basic ideas, and he knew how to ensure they were respected, but at the same time he was open to our suggestions. He incarnated the idea of a legendary figure, almost a great guru.

BAZON BROCK

This multiplicity of points of view enabled the spectator not to find an answer, but to find problems. And thus to become an expert: that means developing the ability to make problems and to criticize. All the curators for d5 were experts in that sense. In the future, educated men and women won’t rely on language, religious beliefs, cultural heritage, ethnic or racial identities that they share to find their social glue; the future glue for social bindings will be extracted out of the common interest in unsolved problems with which mankind is confronted. Artists, since the development of art in the 13th century, have always been problem makers and experts in “problematizing” all the important questions that arise from human beings.

Curators therefore should be able to demonstrate how fruitful the turning toward unsolvable problems could be to open new possibilities. They should give an example of how someone could be able to “earn the fruits of their deeds.”

LUCIA PESAPANE

Can you tell me of other professional experiences you shared with Harald Szeemann?

JEAN-CHRISTOPHE AMMANN

We met in 1961. I was writing about his shows in magazines, and then I started working as an assistant at the Kunsthalle Bern with him until 1968, when I became director of the Kunstmuseum in Lucerne. But we continued to work together.

FRANÇOIS BURKHARDT

I met Harald in the mid 1960s and worked with him and Brock and the Kunsthaus in Hamburg on the concept of the usefulness of art. Szeemann particularly liked this critical approach, not that of an art historian.

BAZON BROCK

Szeemann found in me an authority for his different projects and that meant that asked me to collaborate as an author on five of his major exhibitions. He was interested in people as representatives of ideas and not of social or economic power. He was able even to fruitfully collaborate with individuals who did not agree with his ideas, attitudes, and aims. He honored adversaries as troublemakers or problem generators and we cooperated on this level extremely successfully.

LUCIA PESAPANE

Which aspects of his personality and his accomplishments did you particularly admire?

FRANÇOIS BURKHARDT The show that most moved me was Blood & Honey—The Future is in the Balkans, due to Szeemann’s ability to present vital issues—war, peace, ethnic problems. He had a great freedom of expression, which art constantly needs if it is to truly play its role, which, these days, is overly channeled.

BAZON BROCK

There is no chance for curators, pedagogues, mediators to rely on didactic recipes. Pedagogues never use formalized standards of teaching. Teachers and all the other characters of mediation give examples for operating or handling problems without the ordinary hope of getting rid of problems by solving them. Problems can only be solved by developing new problems. Within the visitor school, the audio-visual preface indicated thematic tours through the exhibition areas and it described the purpose of art as a strategy to turn everything into problems, even self-evident ones. Szeemann, like every scientist, artist, curator, mediator, critic, follows the humanistic program of attitudes become form, if one develops authority by authorship. All the characters mentioned have in common that they are able to argue all by themselves on proposals they make without the help of friends, popes, patriarchs, markets, or other social authorities. In all of his roles as curator, artist, cultural historian, or as one’s contemporary, he aimed to develop authorship and he became a modern type of authority.

[1]

Psychopompo, literally meaning the “guide of souls.” A psychopompo is a mediator between the unconscious and conscious realms. In some cultures, acting as a psychopompo was also one of the functions of a shaman. This could include not only accompanying the soul of the dead, but also vice versa: to help at birth, to introduce the newborn’s soul to the world.