There are two principal attitudes artists adopt towards their times. They can see their cultural production as a counterpoint to the condition and manifestations of the society in which they live, or alternatively they can intervene in this state of affairs with their creative production, thus making it as difficult as possible for their contemporaries to suppress any awareness of what is going on. Winfried Baumann is one of the latter type, whereby the radical nature of his attitude and, hopefully, also the impact of his work is founded on the formal potential that he wields to such a degree as a professional artist, sculptor and architect.

As a contemporary, it is very clear to Baumann that the decisive problems of the consumer society result from our inability to deal adequately with the waste and destructive outcomes of production and consumerism.

But it is precisely those things that we cannot deal with, those that do not comply with our wishes, which define our reality. Things we are unable to deal with make us afraid and define our destiny beyond all individual effort, as an overwhelming reality, these things we must seek to exorcise through ritual.

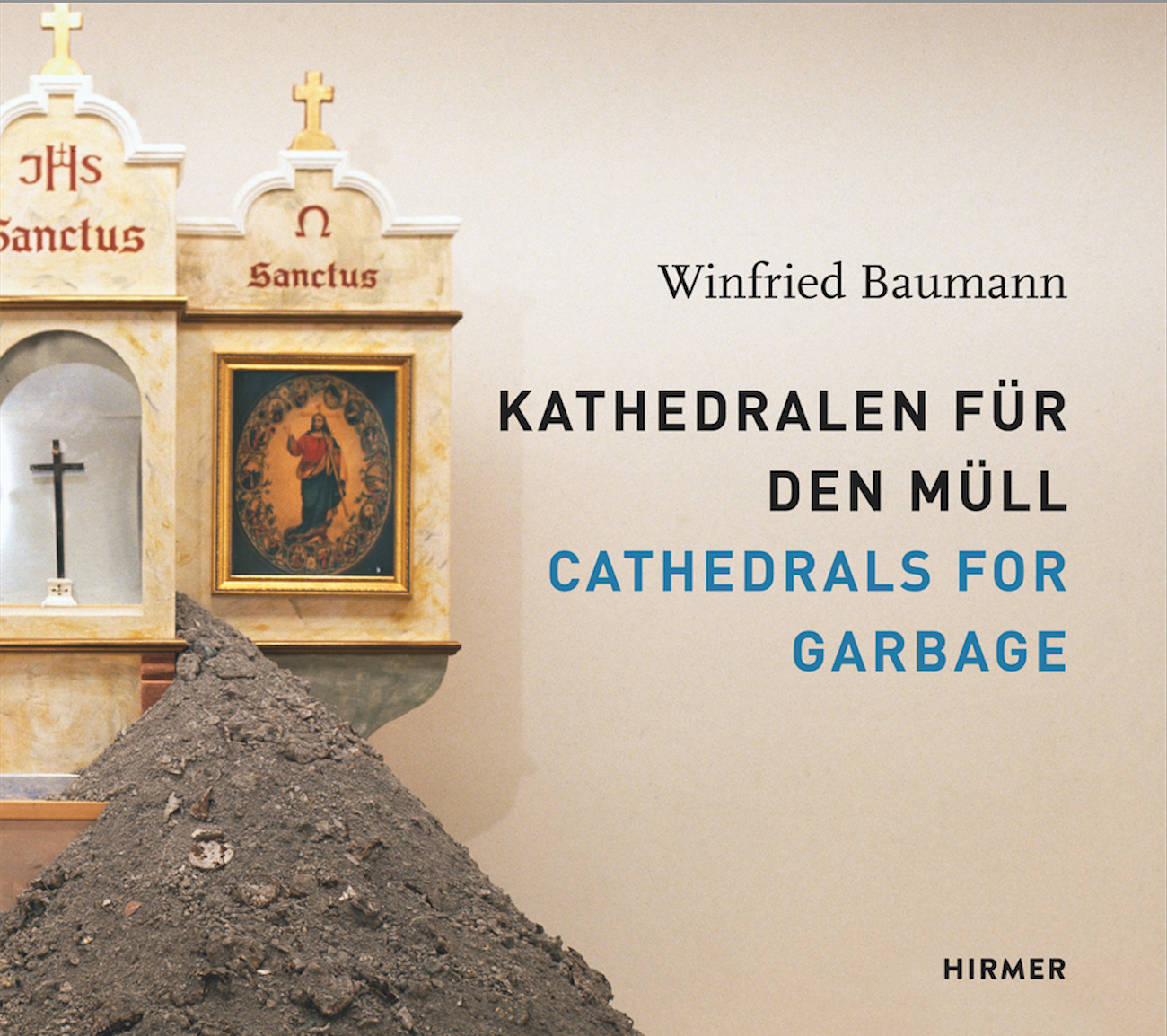

Culture develops such ritual forms at different levels; the most significant being those that attempted, in the shape of religious architecture, to force God, the gods, spirits and ideas into a container, into a delimited area. Nowhere does the demon of our age appear to show itself as so overwhelming and so defining of reality quite as much as in the transformation of the world into an uncontrollable, dead, lunar toxic waste dump, hostile to life.

Baumann constructs cathedrals to this demon, that is, to the obsession we all share, so that the spirit overwhelming us with garbage can perhaps still be compelled to hand over a part of its power to us and we, in exchange, can become ready to acknowledge the refuse and the toxins as our vital force and devote our greatest attention to them. Worship has always been man’s highest form of self-assurance with respect to his destiny. In this regard, there is no distinction for the artist between God and garbage.

The truly convincing aspect of Baumann’s formal conceptions (whether his suggestions for the design of the waste disposal site Atzenhof, those for the architectural re-composition of the government district in Bonn, whether for the design of an altar in a ruinous (!) Gothic cathedral, or restaurant tables for gourmands poisoned by heavy metals) lies in their synthesis of technical functionality and a psychodynamic creation of symbols. In this context, Baumann not only combined the traditional formal languages of Egyptian pyramids and aircraft hangars, for example, in the case of his design for the garbage cathedrals.

The echo of such forms is intended and desirable (monumental religious buildings have always also been dependent on masterly new technical achievements): but to my knowledge, to date no other artist apart from Baumann has found architectural concepts for them. Without doubt, these concepts have evolved from his work as a sculptor, but they are by no means simply monumentalised sculptures. In terms of their symbolic and formal power they are independently projected visions, which in my opinion enable us, for the first time, to experience the holiness of the garbage, toxins and radiation that are defining the fate of humanity.

In the context of Baumann’s concepts for cathedrals of garbage, we can at last engage with our decisive cultural production, that is, the production of death and decay in our cities; we no longer need to banish the deadly and thus worship-worthy filth to areas far from life and underground, or to minimize it through omnipresent distribution, that is to attempt to make it become invisible. The quicker we can acknowledge the deadly, fateful turning of our own works against us, by banishing this self-produced death into cathedrals, the more foundation there will be for hope that these punishing gods will allow themselves to be placated once more.