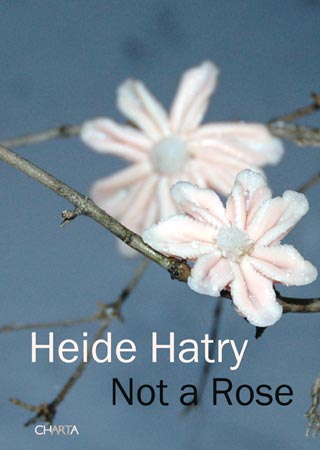

Buch Heide Hatry: Not a Rose

There is no other book that has addressed the meaning of flowers to human beings so diversely, comprehensively, and thoughtfully as Not a Rose. Masked as a traditional coffee table book, it quotes from the genre while turning it inside out, for the images it offers are not innocent pretty flowers but elegant, compelling, and yet grotesque sculptures that the artist has created from the offal, sex organs, and other parts of animals, reminding us that the flowers that grace our homes are really the detached dead sex organs of living beings, and making us question the foundations of aesthetic reception in general.

Woven through the images, and taking its cue from them, is the writing of 101 prominent intellectuals, writers, and artists (such as Jonathan Ames, Steven Asma, Bazon Brock, Karen Duve, Jonathan Safran Foer, Steven Conner, Anthony Haden-Guest, Donna Haraway, Siri Hustvedt, Lucy Lippard, Richard Macksey, Kate Millett, Richard Milner, Hannah Monyer, Rick Moody, Avital Ronell, Stanley Rosen, Steven Pinker, Peter Singer, Justin E. H. Smith, Klaus Theweleit, Luisa Valenzuela, and Franz Wright...) who address “the question of the flower” from a multiplicity of perspectives, including anthropology, philosophy, psychology, sociology, philology, botany, neuroscience, art history, gender studies, physics, and chemistry.

As in her previous conceptual book projects – Skin and Heads and Tales – Hatry has perfected a new form, a hybrid work that is both book and conceptual art installation. Described by legendary artist Carolee Schneemann as an “alchemist of forbidden transmutations, [who] takes our perceptions and pulls them asunder” Hatry follows in the wake of the smartest of the surrealists and the most humane of the conceptualists with work that is both blasphemous and funny, moving and provocative.

In Not a Rose you will experience contemporary art at its best: it is thinking through art.